Originally published on National Geographics Field Notes. The text from my 2019–2021 National Geographics Explorer blog is transcribed here.

Expedition background

Debarati Das is a National Geographic Explorer and a graduate student at McGill University. She studies the geochemistry and habitability of Mars as a member of NASA’s Mars Science Laboratory in collaboration with planetary scientists from Los Alamos National Laboratory and the French National Center for Space Studies. In this video, she talks about her expedition to Death Valley where she and her collaborator Dr. Patrick Gasda went in search for Mars analogue samples.

I’m Debarati Das and I study the chemistry of rocks on Mars as a member of NASA’s Mars Science Laboratory team. I use the data collected by the Martian rover Curiosity and analyze them to understand the composition of the targeted rocks.

Recently, the element boron on Mars was found in mineralized veins within the Martian rocks in Gale crater. This is exciting because boron is a very water-soluble element and can act as a proxy for surface and subsurface water activity on Mars. Looking for water on another planet is a great way to learn about the planet’s habitability and about the possibility of finding signs of alien life. On Earth, boron is known to prolong the stability of ribonucleic acid which is an important molecule for early life. So, finding boron in veins that are associated with water activity, sandwiched between rocks, and are protected from harmful surface UV radiation, has interesting implications from a perspective of possibility of life in hidden pockets on Mars. As boron travels with the water and is left behind when the water dries up, it can even give us clues about the elusive life-story of water on Mars. With our fast-paced strides toward space exploration, it is becoming increasingly vital to understand processes on our own Earth, the most accessible planet for scientific observations. Terrestrial analogues can provide a strong foundation for the understanding of chemical and physical processes that can shed light on the evolution of our neighboring planets. Through my research, I will try to understand the behavior of the element boron in veins of Mars using analogue samples collected from Death Valley in Southern California. Stay tuned to find out more about how we find a portal to Mars right here on Earth!

Staying alive in Death Valley

PREPARATION

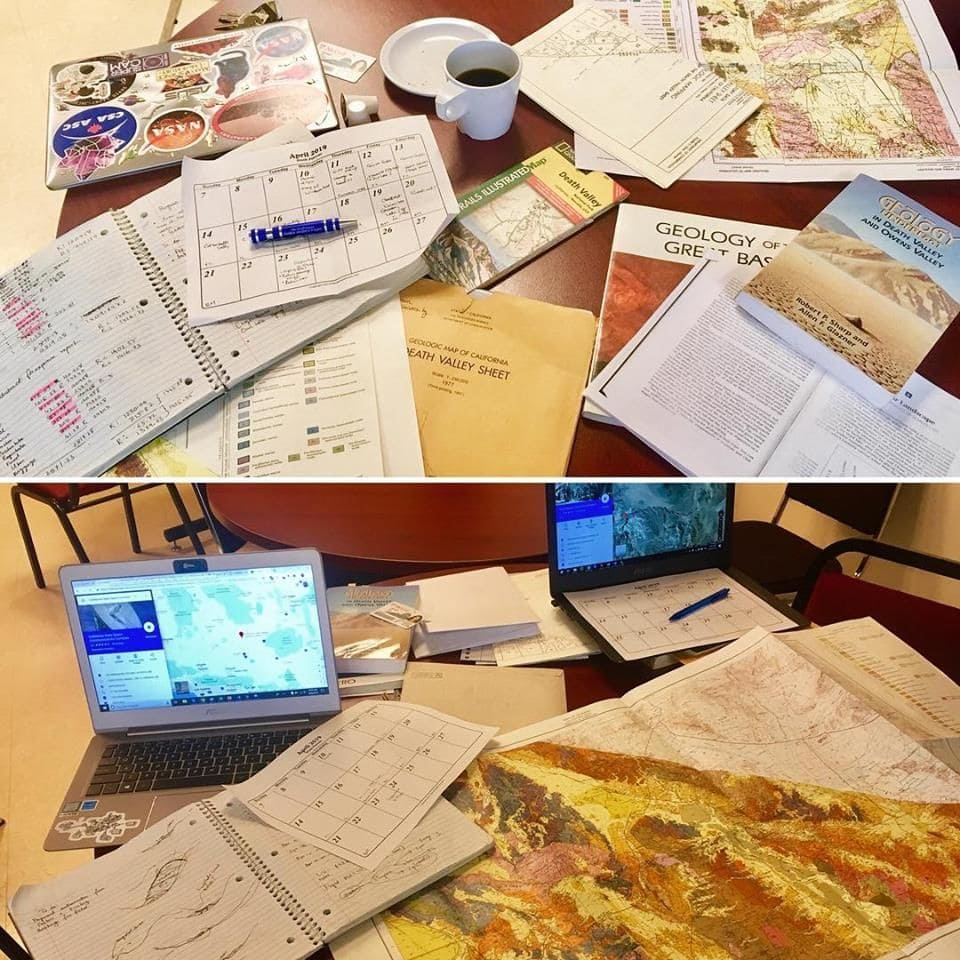

McGill, 845 Rue Sherbrooke Ouest, Montréal, Quebec H3A 0A8, Canada

April 10, 2019

Field prep and recon is important! Especially when you are planning to do geologic fieldwork in a desert valley that reaches some of the highest temperatures on Earth! For the first half of our 15-day expedition to the dry-lake Martian analogues in Southern California, we decided to set camp at the Furnace Creek campground. My camping gear consisted of a tent, a protective tent mat, a sleeping bag, a sleeping mat, camping utensils, multiple water bottles, multiple fruit chews, multiple tubes of high SPF sunscreen and basic toiletries. We borrowed a stove, a large container for food, two 4 gallon containers for water, and two camping chairs from a McGill University Storage unit. I was convinced we were prepared for the hot and dry weather! I was pretty wrong because I completely forgot about the desert dust storms. The first night we spent in Furnace Creek, a dust storm hit at night and covered everything in dust. The wind was so strong, the tent flaps did nothing to protect the inside and we spent half the night holding the tent flaps down and the other half trying to clean sand and dust out of everything. The next day we held the flaps down with rocks and set out for field work and came back to find a new and thick layer of dust on everything inside the tent. This happened so many times, after a few days, we gave up trying to clean the dust. We became one with the dust and truly embraced Death Valley. Our field gear consisted of two hammers, one chisel, two Brunton compasses, two GPS units, two hand lenses and a small bottle of diluted HCl (to check for carbonate rocks). I applied for a sampling permit well in advance, explaining to the national park, the locations of sample collection. (note: sample collection in a national park is strictly prohibited without proper permits) We hired a 4×4 truck, in case we got stuck in the desert sand or in dirt roads which had plenty of storage room for rock samples! Before heading out to field, my field assistant and I did some recon about sampling site selection by looking at maps, we planned out what areas we’ll sample and how we’ll get there. I learned a lot about navigating through new roads and learned a lot about how much more I needed to learn!

Veins of Earth and Mars

Death Valley, California, United States

April 12, 2019

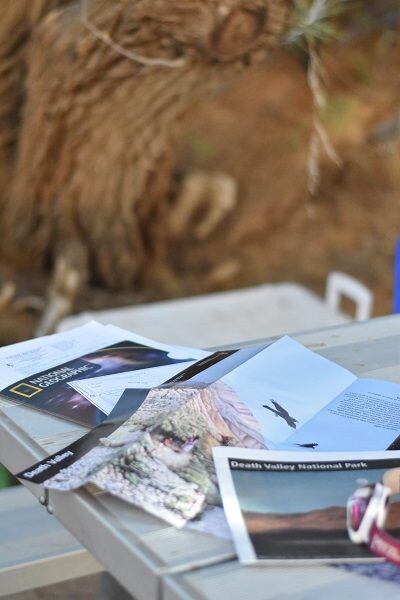

We want answers about veins we observe in rocks of Mars. We want to know how they formed, what was the water like that formed the veins, why do the veins have boron in them, can the boron tell us things about the past water conditions on Mars? So, we packed our incessant questions along with our field gear and took them to Death Valley. We chose Death Valley because it is one of the few candidates that hosts both borate and calcium sulfate deposits in an arid environment with dry-wet cycles like that of Mars. Our field recon shed light on the borate deposits and the interesting human history surrounding the prospecting of these deposits. Our exploration started in the Gower Gulch area of Death Valley National Park. Not long into our first field day, we came across some fantastic looking veins in both alluvial fans and bedrock of the Gulch. We collected vein and surrounding rock samples for detailed analysis. We are curious about the chemical composition of the veins and are looking forward to what we find in the samples of the following field days!

Welcome to Death Valley

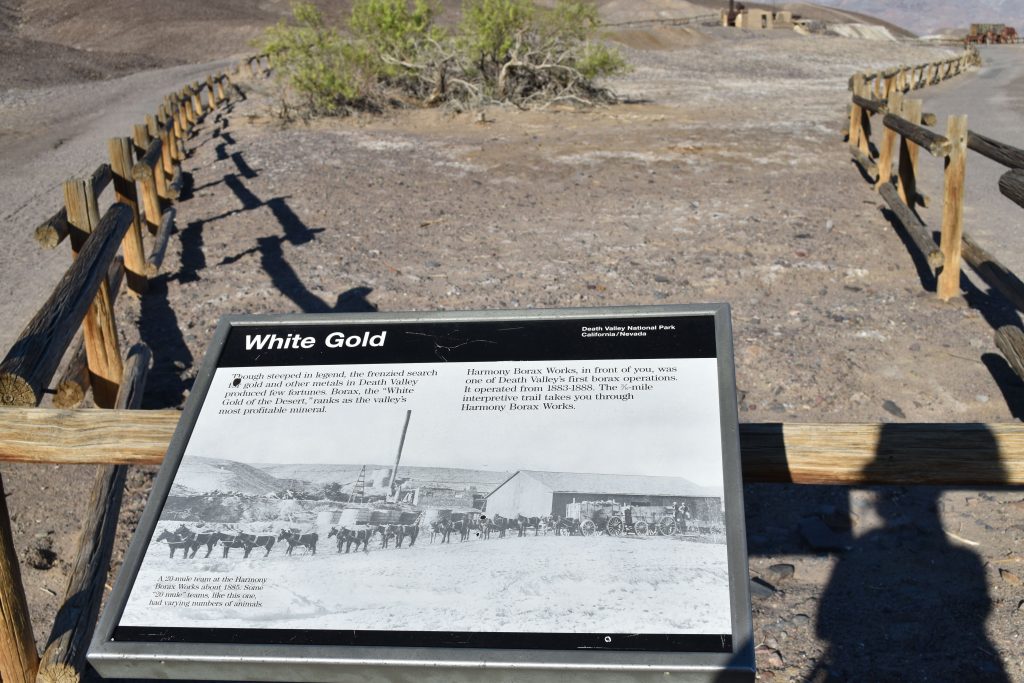

Borates: The White Gold of Southern California

Death Valley, California, United States

April 14, 2019

The story of boron is interesting not only on Mars but also on Earth. In the late 1800s, prospectors came to southern California in Death Valley in search of gold only to find soft, white and often cotton ball-shaped minerals covering acres and acres of the land. They were quick to realize that these white minerals, although not as precious as gold, would become a highly valued commodity in industry and households. This realization gave the white colored borate minerals the name White Gold. In 1882, William T. Coleman built Harmony Borax Works and hired Chinese laborers to scrape cottonball borates from the lake bed in the valley. He also built the Amargosa Borax Works near Shoshone, producing about 2 million pounds of borax per year from his Death Valley and Amargosa borate refineries. 20 Mule Teams were used for hauling millions of pounds of borates from remote desert areas to the railroad at Mojave.

The borates precipitated in the hot summers after the rainwater dissolved and washed down ancient borate deposits from higher elevations to the lake beds in the valley. This process of borate deposition is, in some ways, similar to what we think happened on Mars. But we don’t know for sure yet. So, what better place to look for answers than here?

We made a stop at the Harmony Borax Works on one of our sample collection days. Although we didn’t collect any samples from here (as this site is a preserved area), we did walk around on the interpretive trail and took in the history of the place. It made me think about the fleeting relationship humans have with ancient geologic deposits. Mineral deposits have always been a vital natural resource for us, and they have attracted settlers who depend on mining and prospecting as a livelihood. It was interesting to see the remnants left behind by a community that saw maybe a decade of prosperity in this dry and salty area, then moved away to better prospects, leaving a ghost town in the middle of the desert. But more on that in following blog posts.

The borate deposits surrounding this area are relatively young and are found as flakey crusts on top of dehydrated layers of mud. The ultimate goal of this field season was to collect borates associated with calcium sulfate minerals, but I collected some of these crusty layers too, in case they show us something interesting. I packed them carefully in plastic boxes because I didn’t want the samples to crumble. I’m expecting to see a whole bunch of salt crystals mixed in with whichever borate mineral has precipitated on the mud layers. Samples like these can indicate the properties of the aqueous medium that carried them there then left behind the evaporite minerals once it got hot and dry. This might give us some interesting insights into what ancient aqueous fluids on Mars were like. More updates about the crusty layers to come after some lab work!

Gorgeous Erosional Landscapes at Zabriskie Point

Zabriskie Point, California State Route 190, Death Valley, California 92328, United States

April 15, 2019

Millions of years ago the Amargosa range formed due to tectonic activity that created the mountains and valleys of Southern California. The tectonic activity caused various sedimentary beds that were deposited over millions of years to be exposed to the atmosphere. The contrasting layers seen in the ranges indicate the sedimentary units which likely formed in different depositional environments. The basin and range formation process broke and titled the pre-existing layers enabling us geologists to witness this gorgeous landscape of contrasting colors that took millions and millions of years to form.

The complexity of the patterns on the ranges is further intensified by the process of erosion. These ranges experienced prolonged erosion which caused remobilization of, in some cases sediments and in others, chemicals from the sedimentary layers to bleed into other layers…forming a somewhat diffused appearance of the colorful ranges. The erosion process was probably responsible for leaching out certain chemicals out of the rocks during weather changes or even washing away water-soluble minerals and elements away from the rocks into the valley.

The erosion process is often also responsible for enriching certain types of minerals and elements. In case of the Amargosa Valley, rainfall dissolved water-soluble minerals like borates and chlorides from ancient deposits and redeposited them in the valley. The arid environment of Death Valley promoted the formation of the ubiquitous deposits of secondary borates and salts. As geologists studying borate re-deposition by water on Mars, Death Valley can’t be a better terrestrial analogue! We visited Zabriskie point on our way to sampling on Day 4 because it was close to our campsite and it gave us a wonderful view of potential sampling areas. We collected some really cool samples during our hike through the eroded hills. We found thin layers of evaporite minerals in the alluvial fans by the foot of the hills. These minerals should likely hold geochemical information about the aqueous process that led to their formation. I quickly collected some samples for some exciting lab work!

Ghosts of Death Valley

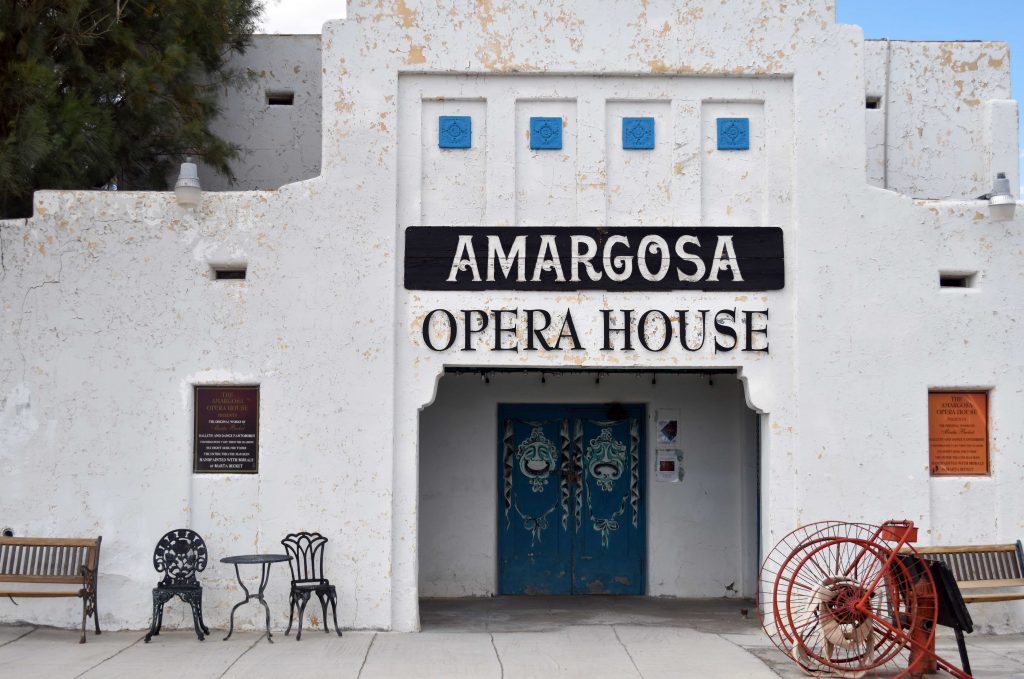

Amargosa Opera House and Hotel, 608 Death Vly Jct, Death Valley, CA, 92328, USA

May 27, 2021

I’ve been wanting to write about an intriguing story about a dancer that I came across while doing my Mars analog fieldwork. No better way to re-start the field stories after a writing hiatus than with a story about Marta Becket.

During field planning, I divided my field work into two parts. The first part consisted of collecting samples in Death Valley and the second part consisted of a mine visit in Boron, south of Death Valley. While we were collecting samples in Death Valley, we set base camp at the Furnace Creek campsite. Every morning we made sure we started super early to beat the mid-morning heat and came back to our tents exhausted and a little dehydrated. On the last day of sample collection in Death Valley, we had only 2 sample sites to visit. So, on our way back, we had time to stop at interesting spots without having to worry about saving energy for hammering rocks and lugging them back.

We had been driving past the Amargosa Opera House every day as we left the campsite for fieldwork, and this day we decided to stop and look around. The Amargosa Opera House and Hotel looked like a structure from another time. The building was covered in white peeling paint and the cracks and paint peels looked more like a design than sun damage. As we walked along the corridor of the building, it felt like ghosts from the past were watching us suspiciously from behind the white lace curtains in the windows. I wondered what the structure looked like in its prime with the Opera House at full capacity. Although this is a strange connection, it also made me think about how trying to imagine Amargosa’s past based on these ghost-towny remnants of a decade of human activity is a little bit like trying figure out the history of Mars based on what is left on Mars today. The place made me think of ancient Mars which was more exciting than a dry inhospitable planet…a warmer, wetter period where exciting things happened, rain filled up lakes and the atmospheric conditions were right to have liquid water on the Martian surface! But now it is like the ghost town I was in with only remnants of a time when life was possible.

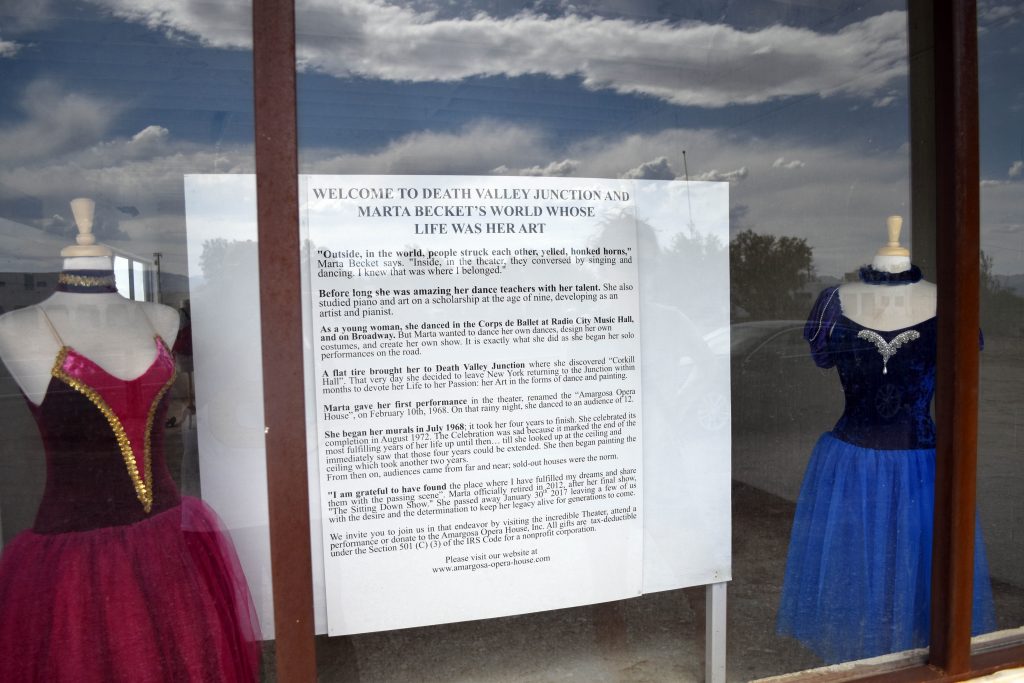

On the other side of the road from the Amargosa Opera house was an enclosed concrete room with large windows you could see the entire room through. In front of each window, inside the concrete room was a mannequin of a torso…the kind they use for sewing which has no head or arms. Each mannequin displayed a unique dress with beautiful colors and fabrics. The dresses looked like costumes for dance performances, and they looked a little out of place against the bare ground of the concrete room and the south-Californian desert. The nearly empty room with headless mannequins with beautiful dresses looked eerie and fascinating. I had so many questions. Thankfully, there were boards next to the mannequins that explained that the dresses belonged to a dancer named Marta Becket.

Marta Becket was a dancer from New York who took a trip to Death Valley and had a flat tire near the Death Valley junction in the 1960s. That is when she discovered the abandoned Corkill Hall. When she peeked through a hole in the door of the hall, Marta felt like the building called out to her asking her to do something with the space. She was inspired to bring the place back to life. She renamed the hall to Amargosa Opera House, painted it, and devoted the rest of her life to performing there. Sometimes she didn’t have a lot of audience, so she painted her own audience on the walls of the hall. She often struggled with the limited resources she had but she worked incredibly hard and inspired many who saw her preform. She brought life and color to Death Valley just like the desert wildflowers did.

When I read that story, at first it felt like a strange thing for a person to do. I feared for her failure although she was no longer alive when I read about her, and I had nothing to do with her life whatsoever. After the initial uncomfortable thoughts, I felt a sort of comfort and inspiration. People have often been fearful about failure for me and have told me not to do things because they are unusual, and that they don’t see me succeeding in my endeavors.

Marta was passionate and she just went ahead and did her thing. It made me think that maybe it’s not about succeeding in all your endeavors. Maybe its about just doing your thing that inspires you to the best of your ability without the constant fear of failure. I felt good having found that story during fieldwork.

Borates of Boron, California helping us understand more about Mars

Boron, CA, USA

June 6, 2021

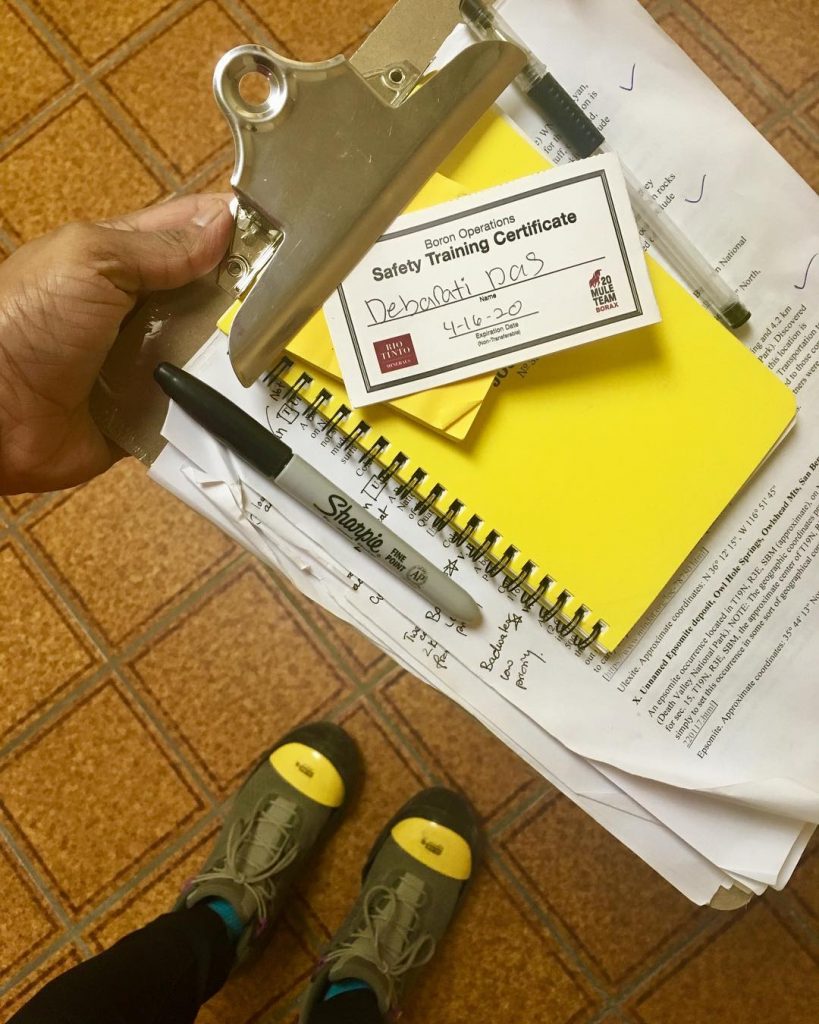

On April 16, 2019, I visited the Rio Tinto Borate mine in Boron, California with my project collaborator Dr. Patrick Gasda, who is a planetary scientist at the Los Alamos National Laboratory, to find out more about how borates form in evaporative environments on Earth. This mine visit was important because it helps us understand why elements like boron and lithium enrich in environments possible on Mars. The mine is a terrestrial analog guide for physical and geochemical processes that could take place on Mars. During field planning I contacted Rio Tinto to obtain permits for sample collection and get guidance form a geologist on their team during the visit. This was exciting because I had never visited a mine before, and this was the first time I got to collect samples from a mine for my research. We arrived at the Rio Tinto facility early and got our safety training certificates before entering the mine area.

Dr. Roberto Torres who is a geologist at Rio Tinto Borates, met us after we got certified and explained the geology of the area to us. After this, all of us got into a car and Dr. Torres started the drive to potential sampling sites and started telling us about the different types of borates and their possible relationship to the surrounding lithology. As we were driving down into the mine, Patrick spotted some vein-like structures on one of the mine walls through the car. We had to stop and get out of the car to get a better look. The mine wall from where we stood, looked like this:

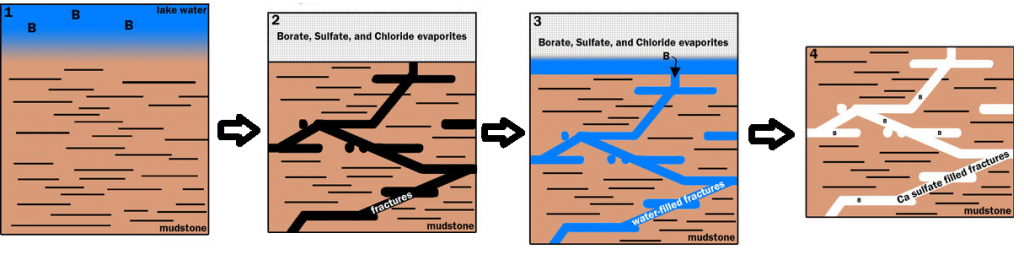

This was a really good spotting because in 2017 when Patrick summarized the results from the first in-situ detection of boron on Mars (in this paper), he predicted a possibility of existence of similar evaporite structures that were remobilized by later generations of water activity (as shown in the image below).

Although this may not be exactly what happened on Mars (as we have not seen any borates on Mars yet), we were thrilled to see these structures. It was nice to be able to see the structures in front of us because it helped us refine the image of possibilities on Mars based on what really does happen on Earth. The parameters on Mars are slightly different but the chemical and physical laws will remain same on both planets. We wanted to take a closer look at the structure, but it wasn’t safe for us to climb up to this area, so we just took a lot of pictures. After spending some time looking at this structure from a distance, we were eager to do some actual sampling. We got back into the car and Dr. Torres started telling us what kind of borates to expect. When we reached the sampling areas, we started spotting the different kinds of borates! Borates are white-ish or clear evaporites so sometimes it is hard to tell them apart. But borates like kernite have a characteristic needle like (or acicular) texture that makes it easy to recognize (and get distracted by because they are also very pretty!). Here is what kernite looks like (the black splotches within the kernite are most likely trapped clay substrate that the kernite was crystallizing near):

The borates we sampled were borax, ulexite, kernite, tincalconite, and howlite. Dr. Torres helped us do a preliminary identification of the borates that were harder to tell apart. We were even able to sample borate veins running through the clay-rich host rock. The samples we collected are very valuable for the research because they help us characterize borates using the ChemCam equivalent laser instrument we use at our labs and help us understand the relationship between the evaporites and the rocks around them. This is harder to do on Mars as the rocks have high amounts of iron oxide (~19 wt%) compared to that of Earth rocks and this interferes with boron signals. Having the access to these samples also means that we can test them using more analytical techniques than possible on the Curiosity rover.

I was so excited to be collecting samples, I didn’t notice the slush next to a mine drainage puddle and stepped right into it. Minor setback. NBD.

After a while of sample collection from different areas in the mine, we spotted a giant block with vein like-structures similar to what we had seen on the mine wall earlier in the day.

We had been wanting to film a video explaining why this visit is important and this seemed like the perfect backdrop for that explanation! You can find video and listen to the explanation below.

More updates soon to come about field and lab analyses.